1. When the Asian immigrant arrives in the U.S., her desire to identify with American national subjects is dislocated and results in alienation. Chinese American scholar Lisa Lowe argues that this is the experience out of which critical subjectivities emerge. Lisa Lowe, “Immigration, Citizenship, Racialization: Asian American Critique,” Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 16-17.

2. ‘Diaspora’ originated as a descriptor for the Jewish people who had been driven to a wandering existence due to their displacement, but has since developed into a widespread term in post-1990s cultural criticism used to refer to diverse other ethnic groups interspersed throughout the world. William Safran, who began the conversation around this concept in the 1990s, characterized diasporas as “expatriate minority communities” and pinpointed an eventual return to the motherland as a defining trait of such communities. William Safran, “Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return,” Diaspora 1, no.1 (Spring 1991): 83-99. Unlike Safran, critical commentators such as Stuart Hall and James Clifford do not presuppose the possibility of return in their conceptualizations of diaspora.

3 . After her death, all of Cha’s work was donated to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) at her alma mater, the University of California, Berkeley, for management purposes and for the establishment of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Archive. BAMPFA spent years on the now completed project of digitizing the material in the archive. It has and continues to provide the principal material for both domestic and international research on Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, in addition to curating major exhibitions around their collection and archive.

4. Cha’s video work exists in dialogue with experimental narrative movements. On the tendencies and attributes of feminist film so classified, refer to Kim Honghee, “A Study on American Feminist Video Art with Emphasis on Narcissism and the Grotesque” (PhD diss., Hongik University, 1997), 116-127.

5. Quoted from “Artist’s Statement,” 1992.4.412, The Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Collection 1971-1991, accessed November 14, 2022, https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf4j49n6h6/?brand=oac4.

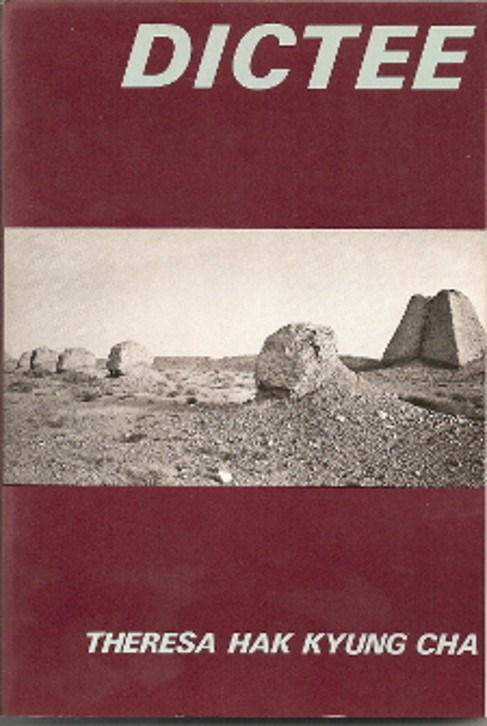

6. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictée (New York: Tanam Press, 1982). Korean American linguist Kim Kyongnyon translated the novel into Korean. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictée, trans. Kim Kyongnyon (Seoul: Tomato, 1997). In 1999, the theater group Mythos staged a dramatization of Dictée entitled The Speaking Woman and submitted it to represent South Korea at the Women Playwrights International Conference the following year.

7. Shirley Geok-lin Lim, et. al., The Forbidden Stitch: An Asian American Women’s Anthology (Corvallis: Calyx, 1989), 70.

8. Quoted in Betty Kano, “Art Essay: Four Northern California Artists: Kisako Hibi, Norine Nishimura, Yong Soon Min, and Miran Ahn,” Feminist Studies 19, no. 3 (Fall 1993): 632.

2. ‘Diaspora’ originated as a descriptor for the Jewish people who had been driven to a wandering existence due to their displacement, but has since developed into a widespread term in post-1990s cultural criticism used to refer to diverse other ethnic groups interspersed throughout the world. William Safran, who began the conversation around this concept in the 1990s, characterized diasporas as “expatriate minority communities” and pinpointed an eventual return to the motherland as a defining trait of such communities. William Safran, “Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return,” Diaspora 1, no.1 (Spring 1991): 83-99. Unlike Safran, critical commentators such as Stuart Hall and James Clifford do not presuppose the possibility of return in their conceptualizations of diaspora.

3 . After her death, all of Cha’s work was donated to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) at her alma mater, the University of California, Berkeley, for management purposes and for the establishment of the Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Archive. BAMPFA spent years on the now completed project of digitizing the material in the archive. It has and continues to provide the principal material for both domestic and international research on Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, in addition to curating major exhibitions around their collection and archive.

4. Cha’s video work exists in dialogue with experimental narrative movements. On the tendencies and attributes of feminist film so classified, refer to Kim Honghee, “A Study on American Feminist Video Art with Emphasis on Narcissism and the Grotesque” (PhD diss., Hongik University, 1997), 116-127.

5. Quoted from “Artist’s Statement,” 1992.4.412, The Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Collection 1971-1991, accessed November 14, 2022, https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf4j49n6h6/?brand=oac4.

6. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictée (New York: Tanam Press, 1982). Korean American linguist Kim Kyongnyon translated the novel into Korean. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictée, trans. Kim Kyongnyon (Seoul: Tomato, 1997). In 1999, the theater group Mythos staged a dramatization of Dictée entitled The Speaking Woman and submitted it to represent South Korea at the Women Playwrights International Conference the following year.

7. Shirley Geok-lin Lim, et. al., The Forbidden Stitch: An Asian American Women’s Anthology (Corvallis: Calyx, 1989), 70.

8. Quoted in Betty Kano, “Art Essay: Four Northern California Artists: Kisako Hibi, Norine Nishimura, Yong Soon Min, and Miran Ahn,” Feminist Studies 19, no. 3 (Fall 1993): 632.

Kim Hyeonjoo

Traversing South Korea and the United States - Diaspora Women Artists Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and Yong Soon Min

Is an artist of Korean origin a Korean artist or an artist who belongs to her country of relocation after she has moved abroad and established a life for herself there? By whom is the answer to said question determined, and does the art world possess an agreed-upon standard through which to ground such an assessment? Do we here hold space for an artist born outside Korea but ethnically Korean? Is there in fact a distinctive character to Korean culture shared between the aforementioned artists and their Korean counterparts? Which of the two exercises the greater weight of authenticity? Are women artists considered to occupy a position representative of the Korean community overseas, or are they once again subject to exclusion from such contexts?

Shaped with Korean American women artists in mind, the questions posited above constitute a reorientation of the issues that began to be posed in earnest under the emerging auspices of multiculturalism, diaspora, post-colonialism, and post-colonial feminism within the U.S. and western European countries that saw a considerable population influx through immigration or migration from formerly colonized nations. These discourses, which surfaced from the late 1980s onward in opposition to hegemonic Western culture, underscored as subjects the immigrants, people of color, and women who experienced marginalization in and from centers of global power and argued for the fresh potential that their creative work embodied in terms of subverting those cultural axes. These conversations gradually expanded to include artists based on the African, Asian, and South American continents, all of which had Western colonial rule carved into their modern histories. These counter discourses unfolded with exceptional vigor in the U.S., where the population of Asian immigrants had surged following the amendments to immigration law passed in 1965. Shored up by such new theories, the Asian American identity discourse and historical narratives which gained ground after the 1980s took a critical approach toward assimilation into majority American society and instead placed unprecedented emphasis on ‘Asianness.’ Putting forth Asianness in a society centered on the white male citizen provided a backbone of oppositional agency and was therefore fundamentally political.1 Even more charged with political significance was the emergence of the Asian American woman as subject, due to her having been doubly marginalized and driven to the peripheries on the basis of gender, race, and ethnicity not only within the dominant society but also by the ethnic community to which she belongs.

Having found its way into multiple exhibitions bridging the United States and the Asian continent, the Asian American identity discourse made its arrival in South Korea known during the 1990s. Across the Pacific: Contemporary Korean and Korean American Art (1993-1994) provided an early example indicative of the shifts in the American art world, its collective introduction to the category of contemporary Korean art situating Minjung art alongside Korean American artists who had been exploring the historical and geopolitical negotiations and issues of identity between the two nations. In a similar vein, the full-fledged introduction of overseas Korean artists within South Korea through exhibitions and research mainly occurred in the 2000s. Exhibitions of note from this period include KOREAMERICAKOREA (2000) at the Art Sonje Center; THERE: Sites of Korean Diaspora (2002), one of the thematic exhibits showcased at the 4th Gwangju Biennale; and The Dream of the Audience: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982) (2003) at Ssamzie Space. These instances represented a break from existing approaches and their preoccupation with biographical and aesthetic inquiry, providing a turning point that viewed overseas Korean artists from the perspective of contemporary counter discourse. They also served as channels through which Min Yong Soon and Jin-me Yoon, both women artists who relocated to the Western North America, maintained ties with the Korean art scene. The late Theresa Hak Kyung Cha was likewise first introduced to South Korean audiences through the KOREAMERICAKOREA exhibition, which showcased her multimedia work Exilée (1980) under the moniker Cha Hakgyeong.

Cha and Min both emigrated to the west coast of the U.S. at around the same period and later became fellow alumni of the University of California, Berkeley in San Francisco. While their families faced different circumstances, these two artists followed a path to the United States which was largely shaped by the political instability of South Korea directly after the April Revolution that brought about the fall of the Rhee Syngman government, as well as the influence of the American Dream and a yearning for the country stationed within Korean society post-liberation. As a nation composed of immigrants, the fundamental condition of assimilating into citizenship involved holding the motherland—in this case, Korea—not as an object to be yearned for and committed to memory but rather as a territory left behind and a past to be forgotten. Nevertheless, Cha and Min on the one hand repudiate the American assimilation which demanded that they erase their motherland from memory and pledge allegiance to their new national home, while on the other remaining cognizant of the futility invoked in both an absolute split from, or repatriation to the motherland. Although they may not renounce notions such as one’s ‘motherland,’ ‘origins,’ and ‘roots’ outright, neither do they regard the motherland as ‘the place to which they (…) would (or should) eventually return,’ choosing instead to underscore the agency of women in the diaspora.2 To spurn a consummate and consolidated subjectivity and redefine the identities of Asian women as belonging neither here nor there is the foundation which both artists share in their work. Cha tied her own narratives to radical and conceptual forms and thereby deconstructed dominant cultural structures and challenged artistic traditions, yet she positioned herself at a distance from the cultural politics of her time. Unlike Cha, however, Min exercised an explicitly political voice, lending an active hand to the formulation and proliferation of identity politics through her creative work and curation.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982) was born in 1951 at the height of the Korean War during a period when her family had evacuated to Busan. In 1963, she followed her parents by way of Hawaii to San Francisco, where she would spend the better part of her life. Her career took off in New York in 1980, but ended when her life was violently and tragically cut short. Though Cha’s years on the art scene were limited, she launched herself into radical artistic forays across all quarters as a video artist, performance artist, conceptual artist, filmmaker, writer, and poet, leaving behind more than fifty pieces of objets d’art, artist books, works on paper, mail art, film/video, and performance records. Held at Ssamzie Space in 2003, The Dream of the Audience: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982) was originally the artist’s first posthumous traveling exhibition, orchestrated and showcased in 2001 by the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), which oversees the entirety of Cha’s work and the archive devoted to her name.3 Korean interest in Cha’s artistry progressed sporadically following the Dream of the Audience exhibition, but Cha has of late gone through something of a rediscovery both domestically and internationally, with the New York Times publishing an obituary in January 2022 forty years after her death and the Whitney Biennial putting her work on view.

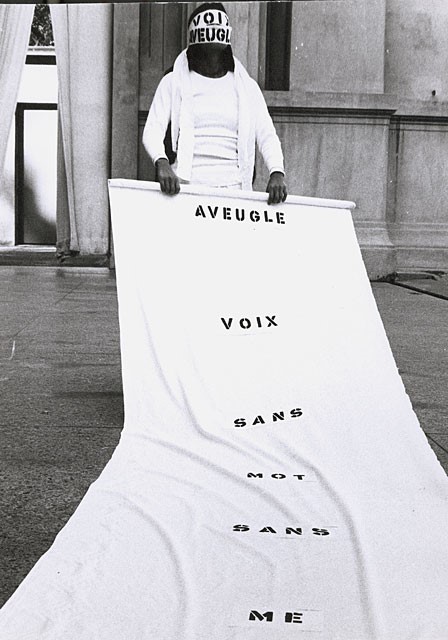

Cha’s work blends elements of conceptual art, semiotics, psychoanalysis, post-colonialism, feminism, and shamanism. If the Asian American rights and feminist cultural movements of the late 1960s in the western U.S. lent form to Cha’s identity, experimental European literature, psychoanalytical schools of thought, and structuralist theory and film with which she familiarized herself while majoring in comparative literature and art spurred forward the aesthetic forms that she adopted. The primary motifs for her work are rooted in a wellspring of autobiographical narrative and experience ingrained with three generations’ worth of history surrounding women’s migration, tracing back to the late Joseon dynasty through Cha’s maternal grandmother and trickling down to Cha’s mother before reaching the artist herself. The artist’s eschewal of realistic depiction, in turn, shares direction with a particular tributary of 1970s feminist video work in its emphasis on film aesthetics and experimental form, its critical approach to filmic structure, and its concern with personal narrative.4 Most of her black-and-white film was structured around long and drawn out pan shots, juxtapositions of freeze frames and text that intimate a sort of movement, and voice-overs in which sound and image fail to correspond. Cha converted and applied film techniques to the grammar of performance and literature and translated the subjects and forms developed in one branch of art into their numerous other counterparts. Such processes of translation created new amalgams and hybrids among different branches of art and thereby transgressed and tested the semantics of the established art world. Exil E E (1980), one of Cha’s most representative film-based pieces, draws on shifts of light and darkness almost too subtle to discern, slow scene executions, and the production of illogical intersections between space and time—the last of which was implemented as part of the new foray into literary writing that yielded Dictée (1982).

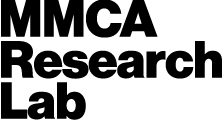

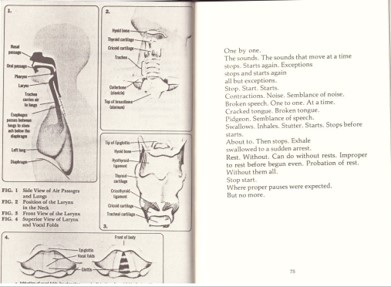

Language is a pivotal concept which runs through Cha’s entire body of work. Borrowing from the artist’s own words, her interests lay in “looking for the roots of the language before it is born on the tip of the tongue” and in “how transformation is brought about through manipulation, processes as changing the syntax, isolation, removing from context, repetition, and reduction to minimal units.”5 Deconstructing the syntactical framework of language accordingly embodies both the subject matter and form of Cha’s work, as we see from the very titles of Vidé o éme (1976) and Exil E E. The operation of splicing English—the official language of the U.S.—together with Korean and French and reconfiguring it to generate new words and forms of meaning offers up the proposition that the relationship between language and geographical location is neither natural nor organic but rather a thing imposed. Cha’s Aveugle Voix (1975) performance uses simple English and French text and the pre-linguistic language of body movement to convey the psychological anguish and crises of identity undergone by the immigrant during the learning and re-learning involved in the language acquisition process.

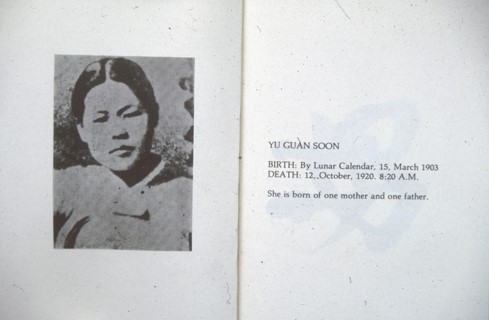

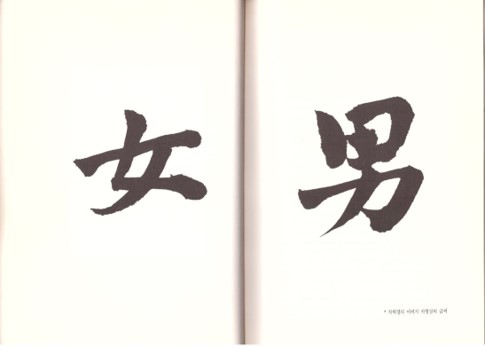

Published immediately after Cha’s death, Dictée (1982) furnishes us with a crucial link as we endeavor to grasp the artist’s pluralistic microcosm and string together the work that she produced through other forms of media.6 The novel features numerous women narrators who roam across spatio-temporal boundaries unfettered, staunchly refusing to present a unified sense of subjectivity and instead putting into practice a rendition of feminine writing that runs counter to masculine writing traditions. The artist employs various images and spaces to create visual collages and adopts film montage techniques and a nonlinear narrative structure to disrupt literary foundations and outstrip fixed literary genres. The radical artistic vision bequeathed to us by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha continues to live on in later generations via the legacy of Dictée.

Yong Soon Min (1953-2024) is a Korean American artist and curator based in Los Angeles. Since the late 1980s, she has been a key contributor to the traction gained by diasporic art and an art activist who aims to bring about social change through art. Having encountered 1980s multiculturalism and feminism centered on people of color, Min joined the Binari group in New York and the Young Korean United in 1986, where she would come to learn of Minjung art and the contemporary political circumstances of Korea, such as the May 18th Democratic Uprising that took place in Gwangju. In 1992, she also witnessed the Los Angeles riots. This sequence of events led Min to focus her attention on South Korea and immigrant society, as well as the geopolitical affiliations between Asia and the U.S. She produced work reflective of Korean American identity within the organic interconnections of race, gender, and class. From the 2000s onward, the artist no longer limited herself to Korean American identity as she gradually extended her interests to Korean and Asian individuals throughout the world, and, in so doing, swept the reach of diasporic art further outward. Min put together the THERE: Sites of Korean Diaspora thematic exhibit for the 2002 Gwangju Biennale, locating and introducing many of the Korean diasporic artists scattered across the globe. In 2007, Min and Vietnamese American scholar Việt Lê co-curated transPOP: Korea Vietnam Remix at the ARKO Art Center to explore the cultural intersections and shifts among the Vietnamese, Korean, and American diasporas following the Vietnam War.

At the beginning of her career in the late 1980s, the artist stated, “My work in art is reflecting my changing awareness as a ‘born-again’ Korean digging deeper into my roots,” implying that she was rediscovering the nation forgotten during the process of assimilation.7 However, it was only a matter of a few years later that she would start questioning “how much of me is Korean, how much has changed, or how much is Americanized and feeling sort of half of both realities, a foot in here, a foot in there,” from which we glean an awareness of the precarious and ambivalent nature of Korean American identity and the futility of a return to the motherland.8 During this period, Min utilized feminine-coded traditional objects such as traditional dress (hanbok), wrapping cloths (bojagi), and Korean bride dolls as signifiers of identity. The traditional dress (hanbok) that appears in Dwelling (1992) and the wrapping cloths (bojagi) of Mother Load (1996) are not motifs that stir up nostalgia or an instinct to return to the motherland. On the contrary, they bring to the fore the ambivalence of identity itself in addition to the history of socio-political strife between Korea and the U.S., the division of Korea, and the history of migration. Furthermore, the body of the artist is at times mobilized as a space inscribed with Asianness and a point of origin for the bifold subordination and internal dislocation of womanhood.

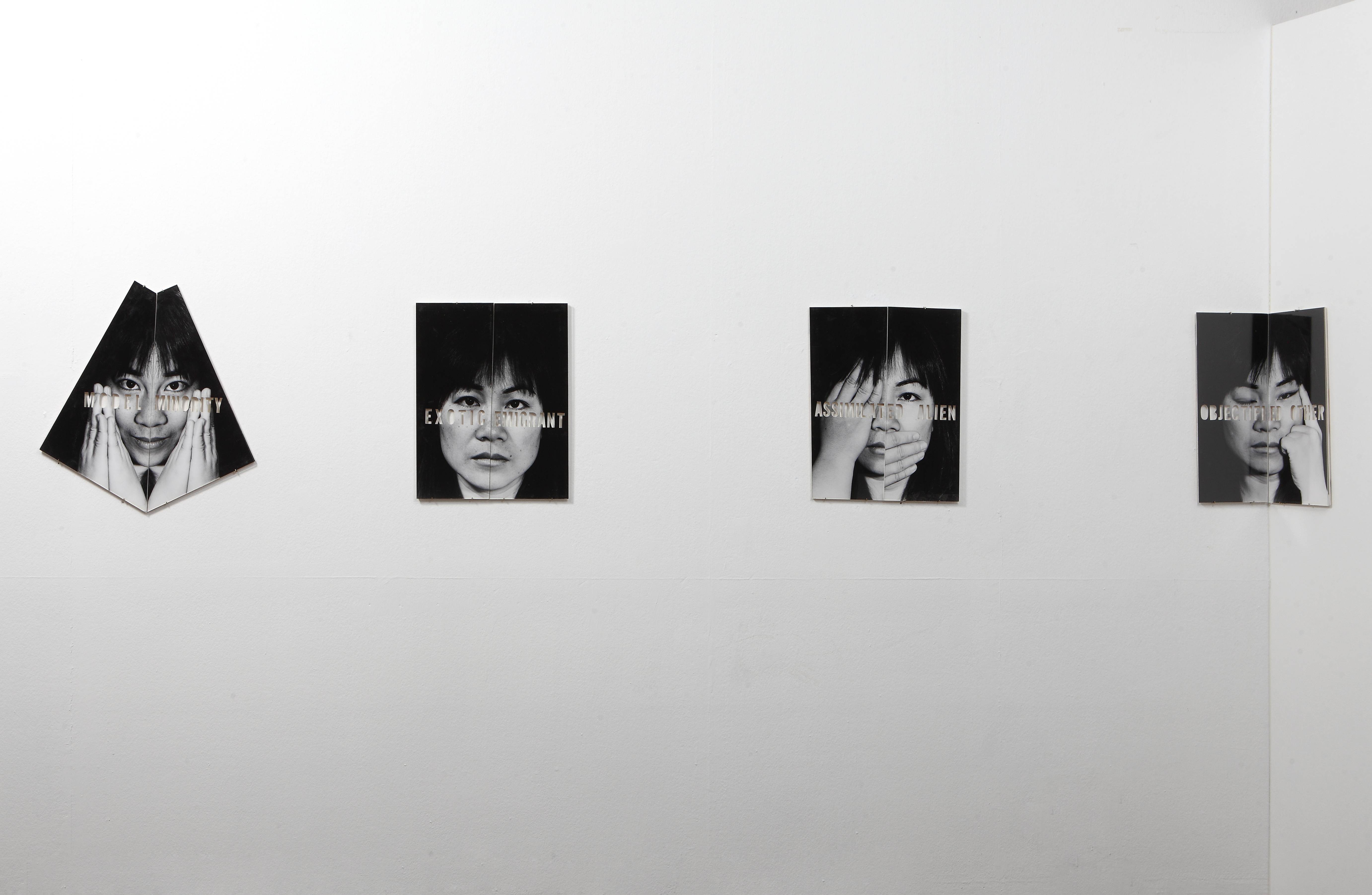

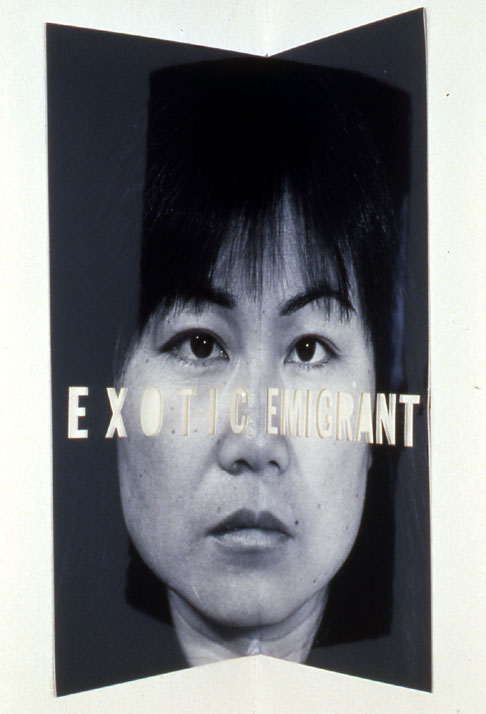

Make Me (1989) is a self-portrait which attempts a paradoxical subversion through an imitation of the preconceived notions concerning Asian women pervasive throughout American society. Cut-out text that reads “Assimilated Alien,” “Exotic Emigrant,” “Objectified Other,” and “Model Minority” overlay four exaggerated and distorted self-portraits. These alliterative phrases spell out the chief strategies formulated for the purpose of pushing Asian women to the margins of American culture, far away from its center of power. The absurd and bizarre cleavage of the artist’s face draws from and negotiates with the inherent logic of dominant social preconceptions—the silence enforced as the price of assimilation, the perpetual placement as romantic object, the internalization of otherness, the idea of being a dominant specimen within an inferior race—ultimately casts off such social expectations. This piece deconstructs and reveals Asian womanhood as a process of fabrication and the utter absence of any essential nature to begin with.

After becoming more aware of North Korea as a distinctive space, Min began to pay particular attention to the two Koreas torn apart from each other, as well as to the motif of the demilitarized zone within the peninsula as emblematic of the history of division. Bridge of No Return (1997) recontextualizes the realities of this division and the artist’s own bearings within history. An aluminum and wood structure—formed with an S-shaped curve that symbolizes yin and yang—marks off the two barbed-wire walls of the military demarcation line and the area in between. The walls on either side indicate the spaces of South and North Korea divided out of one peninsula and speak to the plight of the two countries. One may look toward the other side from their own, but their line of sight is ever refracted, resulting in an impasse of communication. Like the demilitarized zone, the empty middle ground conjoining the two walls belongs neither to the north nor to the south, existing much as a space where the boundaries of either side overlap, cry out to each other, and clash. Just as the title for the piece derives from the “Bridge of No Return” in the demilitarized zone, its initial role is to bring to mind the history of ideological strife between North and South Korea. The “Bridge of No Return” here constitutes an oxymoron in which the standard function of the bridge as a pathway or means of connection is entangled with the implications behind the impossibility of return or revisiting the past. In this sense, the piece operates as a potential metaphor for the diasporic immigrant experience, the middle ground as an analogy for the space ‘in between’ where that which is new germinates from hybridity and conflict and for the identity of the ‘in between’ born out of the diaspora.

Min also discovered that the circumstances surrounding the immigrant laborers in South Korea kindled a deliberation on those of Korean immigrants overseas and accordingly spent a year in Korea visiting the residences and workplaces of numerous immigrant laborers. The film recordings of the interviews conducted during this visit were presented in an exhibition entitled XEN Migration Labor, and Identity (2004). Her consciousness of the severity of the issue having been whetted after the war-time atrocities toward ‘comfort’ women in the history of Japanese colonial rule surfaced in the public eye, the artist launched traditional dress (hanbok) soiled with black tar in Remembering Jungsindae (1993) as an indictment against such violence. Wearing History (2006-2011), showcased for the Nobody exhibition (2014) at the Seoul Museum of Art, once again hearkened back to the subject of comfort women. The piece displayed casual attire stamped with specific years and text and presented said history as a set of bodily memories akin to the clothing that we change in and out of every day.

Teresa Hak Kyung Cha and Young Soon Min have opened up the field of diasporic art by traversing the United States and Korea from the perspective of multi-layered female subjects. The concept of Asian American identity is not a fixed one but is in a state of flux. Young Soon Min, in particular, has voluntarily embraced this change, embodying the relationship between the United States and Asia in the form of art and contributing to the adoption and expansion of the diasporic discourse that is constantly changing in Korea.

Shaped with Korean American women artists in mind, the questions posited above constitute a reorientation of the issues that began to be posed in earnest under the emerging auspices of multiculturalism, diaspora, post-colonialism, and post-colonial feminism within the U.S. and western European countries that saw a considerable population influx through immigration or migration from formerly colonized nations. These discourses, which surfaced from the late 1980s onward in opposition to hegemonic Western culture, underscored as subjects the immigrants, people of color, and women who experienced marginalization in and from centers of global power and argued for the fresh potential that their creative work embodied in terms of subverting those cultural axes. These conversations gradually expanded to include artists based on the African, Asian, and South American continents, all of which had Western colonial rule carved into their modern histories. These counter discourses unfolded with exceptional vigor in the U.S., where the population of Asian immigrants had surged following the amendments to immigration law passed in 1965. Shored up by such new theories, the Asian American identity discourse and historical narratives which gained ground after the 1980s took a critical approach toward assimilation into majority American society and instead placed unprecedented emphasis on ‘Asianness.’ Putting forth Asianness in a society centered on the white male citizen provided a backbone of oppositional agency and was therefore fundamentally political.1 Even more charged with political significance was the emergence of the Asian American woman as subject, due to her having been doubly marginalized and driven to the peripheries on the basis of gender, race, and ethnicity not only within the dominant society but also by the ethnic community to which she belongs.

Having found its way into multiple exhibitions bridging the United States and the Asian continent, the Asian American identity discourse made its arrival in South Korea known during the 1990s. Across the Pacific: Contemporary Korean and Korean American Art (1993-1994) provided an early example indicative of the shifts in the American art world, its collective introduction to the category of contemporary Korean art situating Minjung art alongside Korean American artists who had been exploring the historical and geopolitical negotiations and issues of identity between the two nations. In a similar vein, the full-fledged introduction of overseas Korean artists within South Korea through exhibitions and research mainly occurred in the 2000s. Exhibitions of note from this period include KOREAMERICAKOREA (2000) at the Art Sonje Center; THERE: Sites of Korean Diaspora (2002), one of the thematic exhibits showcased at the 4th Gwangju Biennale; and The Dream of the Audience: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982) (2003) at Ssamzie Space. These instances represented a break from existing approaches and their preoccupation with biographical and aesthetic inquiry, providing a turning point that viewed overseas Korean artists from the perspective of contemporary counter discourse. They also served as channels through which Min Yong Soon and Jin-me Yoon, both women artists who relocated to the Western North America, maintained ties with the Korean art scene. The late Theresa Hak Kyung Cha was likewise first introduced to South Korean audiences through the KOREAMERICAKOREA exhibition, which showcased her multimedia work Exilée (1980) under the moniker Cha Hakgyeong.

Cha and Min both emigrated to the west coast of the U.S. at around the same period and later became fellow alumni of the University of California, Berkeley in San Francisco. While their families faced different circumstances, these two artists followed a path to the United States which was largely shaped by the political instability of South Korea directly after the April Revolution that brought about the fall of the Rhee Syngman government, as well as the influence of the American Dream and a yearning for the country stationed within Korean society post-liberation. As a nation composed of immigrants, the fundamental condition of assimilating into citizenship involved holding the motherland—in this case, Korea—not as an object to be yearned for and committed to memory but rather as a territory left behind and a past to be forgotten. Nevertheless, Cha and Min on the one hand repudiate the American assimilation which demanded that they erase their motherland from memory and pledge allegiance to their new national home, while on the other remaining cognizant of the futility invoked in both an absolute split from, or repatriation to the motherland. Although they may not renounce notions such as one’s ‘motherland,’ ‘origins,’ and ‘roots’ outright, neither do they regard the motherland as ‘the place to which they (…) would (or should) eventually return,’ choosing instead to underscore the agency of women in the diaspora.2 To spurn a consummate and consolidated subjectivity and redefine the identities of Asian women as belonging neither here nor there is the foundation which both artists share in their work. Cha tied her own narratives to radical and conceptual forms and thereby deconstructed dominant cultural structures and challenged artistic traditions, yet she positioned herself at a distance from the cultural politics of her time. Unlike Cha, however, Min exercised an explicitly political voice, lending an active hand to the formulation and proliferation of identity politics through her creative work and curation.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982) was born in 1951 at the height of the Korean War during a period when her family had evacuated to Busan. In 1963, she followed her parents by way of Hawaii to San Francisco, where she would spend the better part of her life. Her career took off in New York in 1980, but ended when her life was violently and tragically cut short. Though Cha’s years on the art scene were limited, she launched herself into radical artistic forays across all quarters as a video artist, performance artist, conceptual artist, filmmaker, writer, and poet, leaving behind more than fifty pieces of objets d’art, artist books, works on paper, mail art, film/video, and performance records. Held at Ssamzie Space in 2003, The Dream of the Audience: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982) was originally the artist’s first posthumous traveling exhibition, orchestrated and showcased in 2001 by the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), which oversees the entirety of Cha’s work and the archive devoted to her name.3 Korean interest in Cha’s artistry progressed sporadically following the Dream of the Audience exhibition, but Cha has of late gone through something of a rediscovery both domestically and internationally, with the New York Times publishing an obituary in January 2022 forty years after her death and the Whitney Biennial putting her work on view.

Cha’s work blends elements of conceptual art, semiotics, psychoanalysis, post-colonialism, feminism, and shamanism. If the Asian American rights and feminist cultural movements of the late 1960s in the western U.S. lent form to Cha’s identity, experimental European literature, psychoanalytical schools of thought, and structuralist theory and film with which she familiarized herself while majoring in comparative literature and art spurred forward the aesthetic forms that she adopted. The primary motifs for her work are rooted in a wellspring of autobiographical narrative and experience ingrained with three generations’ worth of history surrounding women’s migration, tracing back to the late Joseon dynasty through Cha’s maternal grandmother and trickling down to Cha’s mother before reaching the artist herself. The artist’s eschewal of realistic depiction, in turn, shares direction with a particular tributary of 1970s feminist video work in its emphasis on film aesthetics and experimental form, its critical approach to filmic structure, and its concern with personal narrative.4 Most of her black-and-white film was structured around long and drawn out pan shots, juxtapositions of freeze frames and text that intimate a sort of movement, and voice-overs in which sound and image fail to correspond. Cha converted and applied film techniques to the grammar of performance and literature and translated the subjects and forms developed in one branch of art into their numerous other counterparts. Such processes of translation created new amalgams and hybrids among different branches of art and thereby transgressed and tested the semantics of the established art world. Exil E E (1980), one of Cha’s most representative film-based pieces, draws on shifts of light and darkness almost too subtle to discern, slow scene executions, and the production of illogical intersections between space and time—the last of which was implemented as part of the new foray into literary writing that yielded Dictée (1982).

Language is a pivotal concept which runs through Cha’s entire body of work. Borrowing from the artist’s own words, her interests lay in “looking for the roots of the language before it is born on the tip of the tongue” and in “how transformation is brought about through manipulation, processes as changing the syntax, isolation, removing from context, repetition, and reduction to minimal units.”5 Deconstructing the syntactical framework of language accordingly embodies both the subject matter and form of Cha’s work, as we see from the very titles of Vidé o éme (1976) and Exil E E. The operation of splicing English—the official language of the U.S.—together with Korean and French and reconfiguring it to generate new words and forms of meaning offers up the proposition that the relationship between language and geographical location is neither natural nor organic but rather a thing imposed. Cha’s Aveugle Voix (1975) performance uses simple English and French text and the pre-linguistic language of body movement to convey the psychological anguish and crises of identity undergone by the immigrant during the learning and re-learning involved in the language acquisition process.

Published immediately after Cha’s death, Dictée (1982) furnishes us with a crucial link as we endeavor to grasp the artist’s pluralistic microcosm and string together the work that she produced through other forms of media.6 The novel features numerous women narrators who roam across spatio-temporal boundaries unfettered, staunchly refusing to present a unified sense of subjectivity and instead putting into practice a rendition of feminine writing that runs counter to masculine writing traditions. The artist employs various images and spaces to create visual collages and adopts film montage techniques and a nonlinear narrative structure to disrupt literary foundations and outstrip fixed literary genres. The radical artistic vision bequeathed to us by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha continues to live on in later generations via the legacy of Dictée.

Yong Soon Min (1953-2024) is a Korean American artist and curator based in Los Angeles. Since the late 1980s, she has been a key contributor to the traction gained by diasporic art and an art activist who aims to bring about social change through art. Having encountered 1980s multiculturalism and feminism centered on people of color, Min joined the Binari group in New York and the Young Korean United in 1986, where she would come to learn of Minjung art and the contemporary political circumstances of Korea, such as the May 18th Democratic Uprising that took place in Gwangju. In 1992, she also witnessed the Los Angeles riots. This sequence of events led Min to focus her attention on South Korea and immigrant society, as well as the geopolitical affiliations between Asia and the U.S. She produced work reflective of Korean American identity within the organic interconnections of race, gender, and class. From the 2000s onward, the artist no longer limited herself to Korean American identity as she gradually extended her interests to Korean and Asian individuals throughout the world, and, in so doing, swept the reach of diasporic art further outward. Min put together the THERE: Sites of Korean Diaspora thematic exhibit for the 2002 Gwangju Biennale, locating and introducing many of the Korean diasporic artists scattered across the globe. In 2007, Min and Vietnamese American scholar Việt Lê co-curated transPOP: Korea Vietnam Remix at the ARKO Art Center to explore the cultural intersections and shifts among the Vietnamese, Korean, and American diasporas following the Vietnam War.

At the beginning of her career in the late 1980s, the artist stated, “My work in art is reflecting my changing awareness as a ‘born-again’ Korean digging deeper into my roots,” implying that she was rediscovering the nation forgotten during the process of assimilation.7 However, it was only a matter of a few years later that she would start questioning “how much of me is Korean, how much has changed, or how much is Americanized and feeling sort of half of both realities, a foot in here, a foot in there,” from which we glean an awareness of the precarious and ambivalent nature of Korean American identity and the futility of a return to the motherland.8 During this period, Min utilized feminine-coded traditional objects such as traditional dress (hanbok), wrapping cloths (bojagi), and Korean bride dolls as signifiers of identity. The traditional dress (hanbok) that appears in Dwelling (1992) and the wrapping cloths (bojagi) of Mother Load (1996) are not motifs that stir up nostalgia or an instinct to return to the motherland. On the contrary, they bring to the fore the ambivalence of identity itself in addition to the history of socio-political strife between Korea and the U.S., the division of Korea, and the history of migration. Furthermore, the body of the artist is at times mobilized as a space inscribed with Asianness and a point of origin for the bifold subordination and internal dislocation of womanhood.

Make Me (1989) is a self-portrait which attempts a paradoxical subversion through an imitation of the preconceived notions concerning Asian women pervasive throughout American society. Cut-out text that reads “Assimilated Alien,” “Exotic Emigrant,” “Objectified Other,” and “Model Minority” overlay four exaggerated and distorted self-portraits. These alliterative phrases spell out the chief strategies formulated for the purpose of pushing Asian women to the margins of American culture, far away from its center of power. The absurd and bizarre cleavage of the artist’s face draws from and negotiates with the inherent logic of dominant social preconceptions—the silence enforced as the price of assimilation, the perpetual placement as romantic object, the internalization of otherness, the idea of being a dominant specimen within an inferior race—ultimately casts off such social expectations. This piece deconstructs and reveals Asian womanhood as a process of fabrication and the utter absence of any essential nature to begin with.

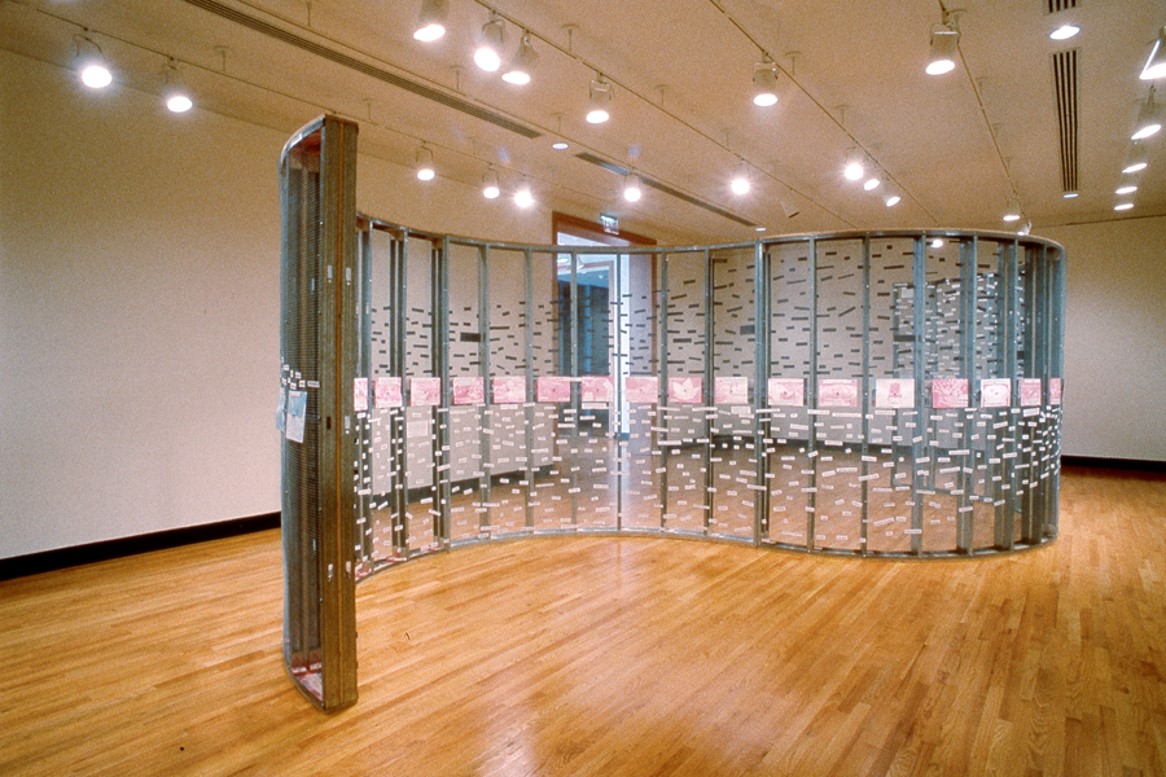

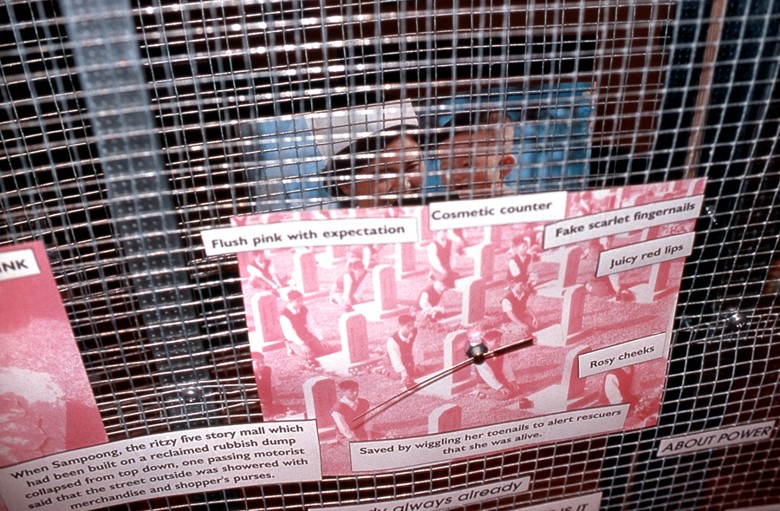

After becoming more aware of North Korea as a distinctive space, Min began to pay particular attention to the two Koreas torn apart from each other, as well as to the motif of the demilitarized zone within the peninsula as emblematic of the history of division. Bridge of No Return (1997) recontextualizes the realities of this division and the artist’s own bearings within history. An aluminum and wood structure—formed with an S-shaped curve that symbolizes yin and yang—marks off the two barbed-wire walls of the military demarcation line and the area in between. The walls on either side indicate the spaces of South and North Korea divided out of one peninsula and speak to the plight of the two countries. One may look toward the other side from their own, but their line of sight is ever refracted, resulting in an impasse of communication. Like the demilitarized zone, the empty middle ground conjoining the two walls belongs neither to the north nor to the south, existing much as a space where the boundaries of either side overlap, cry out to each other, and clash. Just as the title for the piece derives from the “Bridge of No Return” in the demilitarized zone, its initial role is to bring to mind the history of ideological strife between North and South Korea. The “Bridge of No Return” here constitutes an oxymoron in which the standard function of the bridge as a pathway or means of connection is entangled with the implications behind the impossibility of return or revisiting the past. In this sense, the piece operates as a potential metaphor for the diasporic immigrant experience, the middle ground as an analogy for the space ‘in between’ where that which is new germinates from hybridity and conflict and for the identity of the ‘in between’ born out of the diaspora.

Min also discovered that the circumstances surrounding the immigrant laborers in South Korea kindled a deliberation on those of Korean immigrants overseas and accordingly spent a year in Korea visiting the residences and workplaces of numerous immigrant laborers. The film recordings of the interviews conducted during this visit were presented in an exhibition entitled XEN Migration Labor, and Identity (2004). Her consciousness of the severity of the issue having been whetted after the war-time atrocities toward ‘comfort’ women in the history of Japanese colonial rule surfaced in the public eye, the artist launched traditional dress (hanbok) soiled with black tar in Remembering Jungsindae (1993) as an indictment against such violence. Wearing History (2006-2011), showcased for the Nobody exhibition (2014) at the Seoul Museum of Art, once again hearkened back to the subject of comfort women. The piece displayed casual attire stamped with specific years and text and presented said history as a set of bodily memories akin to the clothing that we change in and out of every day.

Teresa Hak Kyung Cha and Young Soon Min have opened up the field of diasporic art by traversing the United States and Korea from the perspective of multi-layered female subjects. The concept of Asian American identity is not a fixed one but is in a state of flux. Young Soon Min, in particular, has voluntarily embraced this change, embodying the relationship between the United States and Asia in the form of art and contributing to the adoption and expansion of the diasporic discourse that is constantly changing in Korea.

- Share

Copy URL

Copy URL

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Aveugle Voix, 1975, Picture, 63 Bluxome Street, San Francisco. Online Archive of California.

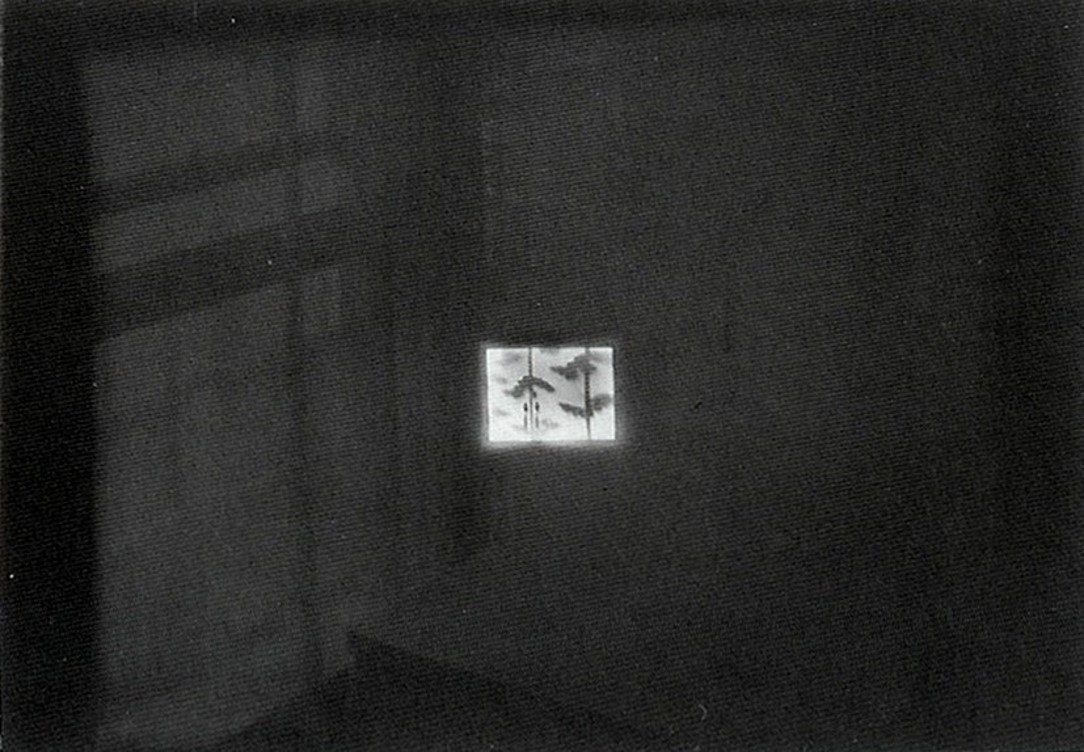

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Exilée, 1980, 8mm film and video installation, sound, 43min. Online Archive of California.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Exilée, 1980, 8mm film and video installation, sound, 43min. Online Archive of California.

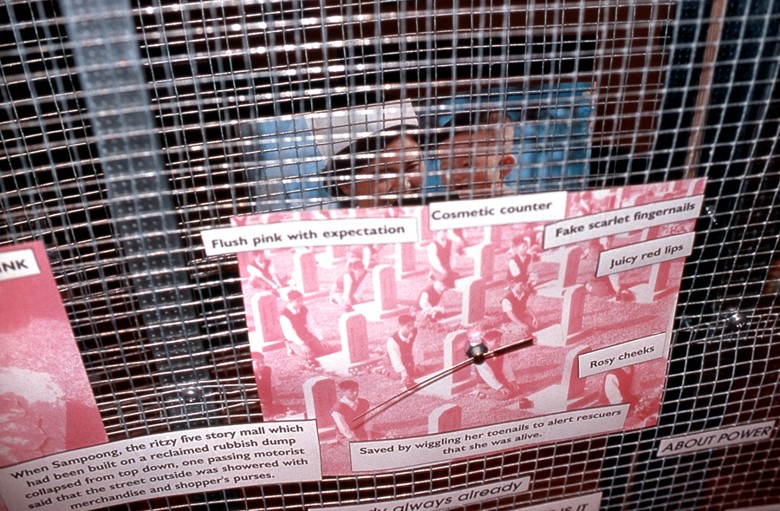

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictée, Tanam Press, 1982. Photo: Kim Hyeonjoo.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictée, Tanam Press, 1982. Photo: Kim Hyeonjoo.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictée, Tanam Press, 1982. Photo: Kim Hyeonjoo.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictée, Tanam Press, 1982. Photo: Kim Hyeonjoo.

Yong Soon Min, Make Me, 1989, Gelatin silver print, 68.5×58.4cm (4). SeMA.

Yong Soon Min, Make Me, 1989, Gelatin silver print, 68.5×58.4cm (4). SeMA.

Yong Soon Min, Bridge of No Reutrn, 1997.

Yong Soon Min, Bridge of No Reutrn, 1997.

Yong Soon Min, Wearing History, 2006-2011, 2014 SeMA Gold Nobody Exhibition view.