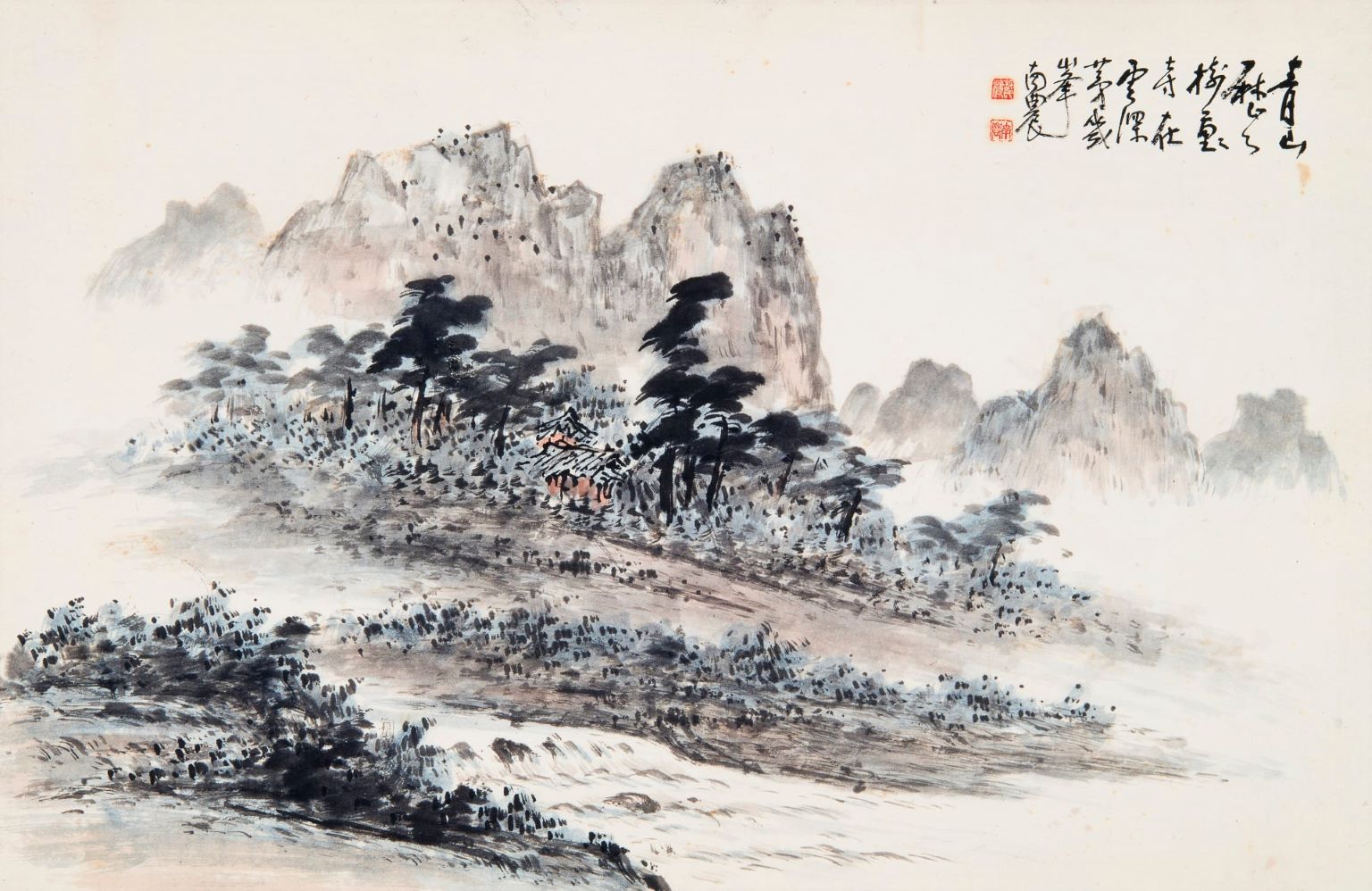

Bae Ryeom, Landscape, Ink on paper, 90×139cm. MMCA collection

Bae Ryeom

* Source: Multilingual Glossary of Korean Art by Korea Arts Management Service

Related

-

Eastern painting

Eastern painting (dongyanghwa) refers to the overall body of works created using traditional East Asian materials and methods, in contrast to Western painting. In Korea, Byeon Yeongro’s essay “On Eastern Painting” published in Dong-A Ilbo on 7th, July, 1920 was the first use of the term. The term then began to be used in Japan first to distinguish Oriental style paintings from Western ones. Until the late Joseon era, both calligraphy and painting were categorized under the term seohwa, but during the Japanese occupation of Korea in 1922, the first Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe] divided the painting section into Western and Eastern styles. Thereafter, the term Eastern-style painting entered official use in the country. After independence, the National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon) continued to use the term “Eastern painting,” but since 1970, numerous arguments were made to replace it with "Korean painting," because the term was imposed unilaterally during the Japanese colonial era.

-

Dangu Art Academy

A Seoul-based art institute formed directly after national independence in 1945, by Lee Ungno, Chang Woosoung, Lee Yootae, Bae Ryeom, Kim Youngki, Cho Joonghyun, Jeong Honggeo, Chung Chincheol, and Cho Yongseung. The purpose of this academy was to reduce the Japanese influence on Korean art and to restore cultural legitimacy to traditional painting. The academy closed following a 3rd joint exhibition in 1948. The academy is significant in that it pursued a different and nationally specific perspective on Korean art following independence.

-

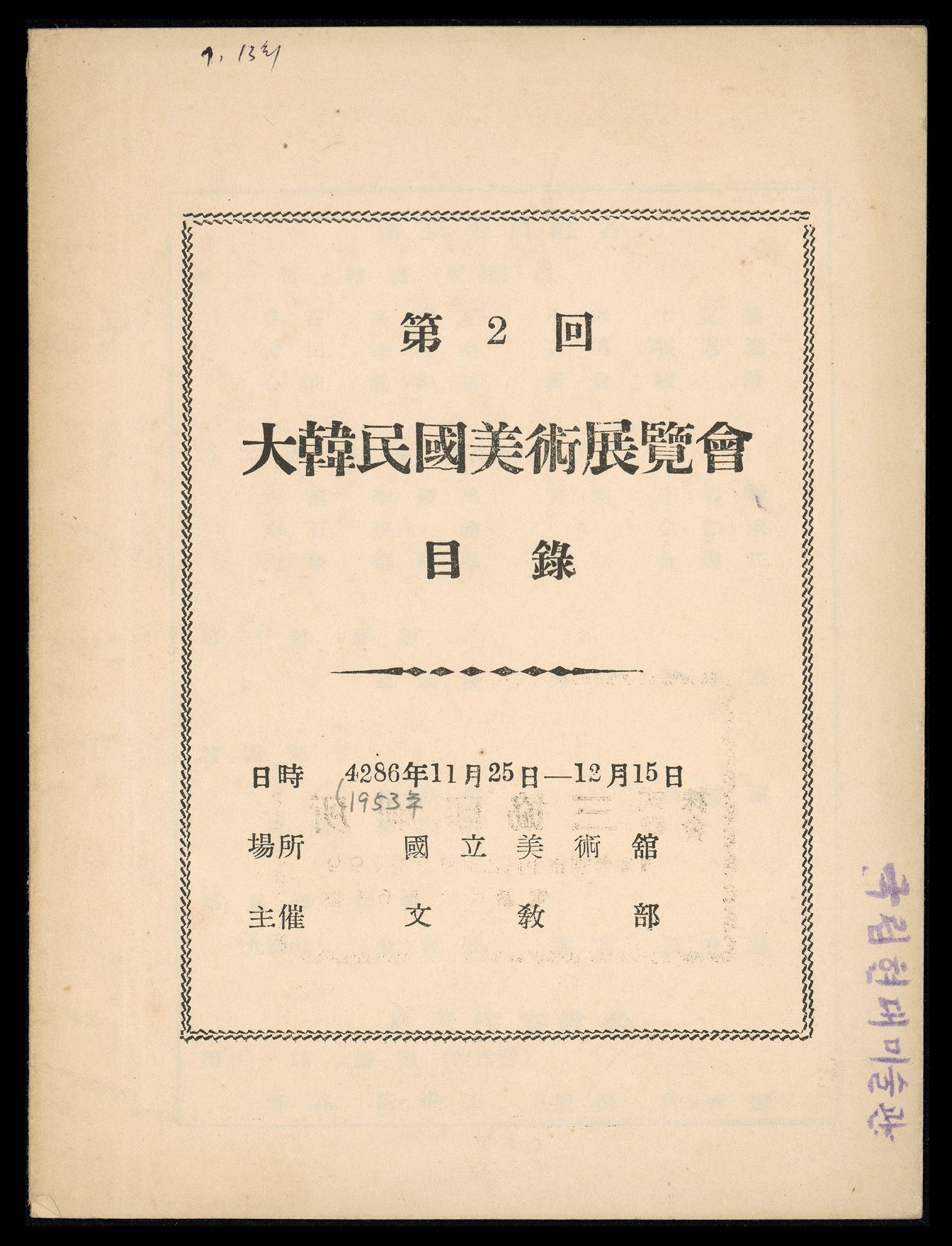

National Art Exhibition

A government-hosted exhibition held 30 times from 1949 to 1981, also known by the shorter name Gukjeon. Following national independence, the exhibition was the primary means for young and emergent Korean artists to achieve recognition. The influence of the exhibition declined as a result of the emergence of non-figurative art during the 1970s, the increased opportunities for artists to participate in overseas exhibitions, and the rise of private exhibitions and galleries.

Find More

-

The National Academy of Arts, Republic of Korea

An organization established in July 1954 to support artists who have been recognized as making a significant contribution to the arts at a national level. The organization is also responsible for advising the government on policies for the advancement of the arts, supporting the creative endeavors of artists in general, engaging in international exchanges and exhibitions, and hosting events. The academy has four divisions: literature, art, music, and performing arts/film/dance. The current membership numbers at 100.

-

Lee Sangbeom

Lee Sangbeom (1897-1972, pen name Cheongjeon) learned painting from An Jungsik and Cho Seokjin at the Calligraphy and Painting Society [Seohwa misulhoe] and graduated in 1918. He became a member of the Calligraphy and Painting Association [Seohwa hyeophoe] founded in 1918 and submitted his work to the first Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe] in 1922. He repeatedly won special prizes and was appointed as a Noteworthy Artist and Participating Artist of Eastern painting in the Joseon Art Exhibition. In 1920, he participated in the Changdeokgung Palace mural project and created the work Samseongwanpado. He founded the Cheongjeon Art Studio to educate art students in 1933 and gained notoriety by contributing illustrations to serialized pro-Japanese newspaper novels. After independence, he was accused of being pro-Japanese, but continued to focus on his art nonetheless, becoming an important figure in art circles. In the 1950s, he created his own original ‘Cheongjeon’ style. This Korean-style landscape ink wash painting was based on real Korean scenery and represented what many consider as the essential aesthetics of Korean landscape painting. While he consistently participated in the National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon), he never hosted a solo exhibition of his own, and in terms of his teaching in the post-independence period he taught as an art professor at Hongik University.

-

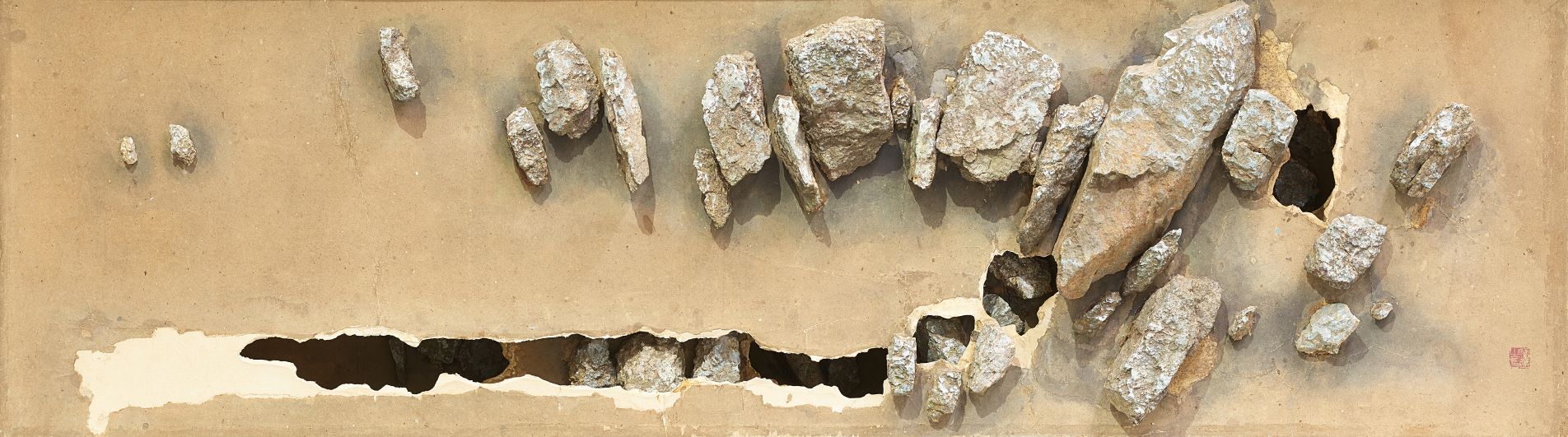

Ahn Sangchul

Ahn Sangchul (1927-1993, pen name Yeonjeong) is a painter who pioneered the expressive realm of Korean painting with his experimental work. He graduated from the Department of Painting at Seoul National University. In 1953, his last year of university, Ahn received an honorable mention for his Late Autumn at the Second National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon). His Field and Transquility won the Minister of Education Award in 1956 and 1957, respectively. Moreover, his The Remaining Snow and Clear Day earned him a Vice-Presidential Award and a Presidential Award in 1958 and 1959, respectively. Ahn learned traditional landscape painting from Noh Soohyun, Chang Woosoung, and Bae Ryeom at the university. However, his bold compositions and his drastic wielding of ink and brush in combination with Western visual principles brought attention to his Eastern-style paintings that broke away from traditional paintings. Ahn sought the modernization of Eastern painting by actively embracing Art Informel pursued by Korean painting circles in the 1950s. From the 1960s onward, he produced abstract paintings, such as Full of Charming Dreams (1960) and Mong Mong Chun (Spring in hazy dreams) (1961). Later, he continued to experiment with objets and materials like stone or kraft paper and released the three-dimensional, abstract Spirit series that transcended the flatness of painting. He served as a judge for Gukjeon and a member and chairman of its operating committee. He was the youngest Gukjeon judge. He also worked as a professor at the Seorabeol University of Arts and Sungshin Women’s University.